Tosiuti ni Nasukoto no Aya, Season of To, Ikeda 2017, p121

The Seasons of the Motoake

We continue through the seasons of the Motoake. After Ye no Kami in the previous post come the Kami Hi, Ta, Me, … clockwise around the Motoake circle of time (below).

Let us turn our attention to what the Tosiuti has to say about To no Kami.

The Season of To (post summer solstice)

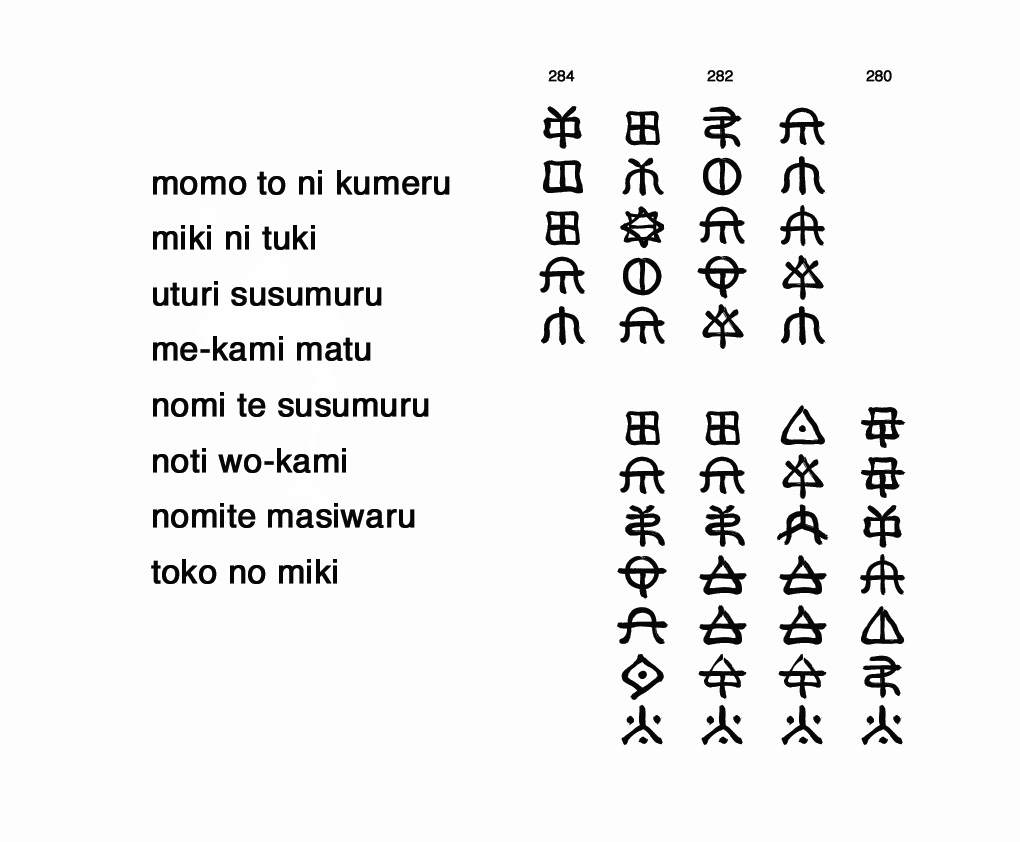

To is the kami for the late summer season which begins the day of summer solstice. The following lines appear in 7.3 – 7.8 (above chart):

….. To wa sa ni yi ma su

me ya wa ka mi — mi tu no hi ka ri no

sa tu ki na ka — hi to me hu si o ki

sa mi ta ru ru — yo ro no a o ba no

ka ze ka ho ru …

To wa sa ni yimasu (To is in the south), for summer solstice (usually June 21) has come. The sun is highest in the sky and it is warm. This is the time the sun casts the shortest shadows. It is warmer even underground. During the month of satsuki (June), the rainy season brings forth many green leaves (yoro no ao ba). On the breeze is their fragrance (kaze kahoru) which flows through the dwellings and gives long life.

Lines 7.8-8.4:

mi ya ni o ku re ba

na ga ra ye ri — me ha ha ni mi te do

u ye a tu ku — mi na tu ki su ye ha

i yo ka wa ki — mo mo ni ti ma tu ru

ti no wa nu ke — yi so ra o ha ra hu

The rainy season is over by suye (end) of minatsuki (July) and the land dries out. It is time for making tinowa (chinowa).

Tinowa (chinowa) is the large wreath in front of a shrine in the summer that people go through for purification. See photo at bottom. Chimaki (mochi wrapped in a leaf) is eaten for purification. These summer observances drive out the negative energies of the yisora-kami. Both the chinowa and the chimaki are made with the leaves of the kaya plant.

Chimaki: mochi wrapped in a kaya leaf. Photo credit here.

Next, lines 8.5 – 8.7 appear:

… ka ta ti ha ku ni no

na ka ha si ra — ma ye ni to to na hu

To mo to ka mi.

This is the practice of To-no-mikoto (To-moto-kami), who was the second Amakami.

To, we were told, is in the south. Then the aya goes on to Ho no Kami (early autumn), line 8.7:

Ho wa ki ne ni su mu

Ho lives in ki-ne (north-east). See the Motoake directional chart from the Motoake post, shown again here. Then the aya talks about Ka and Mi, which takes us back to Ye.

We will close this summer post with lines 9.3-9.4:

ta ku ha ta ya — A wa no ho gi u ta

ka yi ni o si — si mu no mo ti ho gi

…

Ikeda says that takuhata is the same as tanahata (tanabata), the maturi of the seventh night of the seventh month (August 7). Apparently tanahata maturi was important in Wosite times. It is mentioned more than once in the Wosite documents, including Aya 1 of the Hotuma Tutaye.

Note. In case you are wondering about the conversion into our Gregorian months, we point out that the old calendar was a lunar calendar, and the “seventh month” converts into the eighth Gregorian month.

Chinowa in front of Taga Taisha, June 23, 2012. Photo by WoshiteWorld

***

Namekoto no Aya by Yasutoshi Waniko,courtesy Japan Translation Center

Namekoto no Aya by Yasutoshi Waniko,courtesy Japan Translation Center