LECTURE 2 TIME, SPACE AND WEAVING THE UNIVERSE

Preface

Okunomichi on 2014.09.04 presented a brief overview, Kototama Researchers of the Modern Period. Kototama is the soul of words as well as the soul of things, and therefore the sacred power of speech. We have devoted several posts to this topic on this site and on Okunomichi, and they can be located through the SEARCH box. As promised long ago, we are now posting notes from the lectures of Yamakoshi Meisho (aka Yamakoshi Akimasa). From Okunomichi:

Yamakoshi Hiromichi (Koudo), Calligrapher to Emperor Meiji

Yamakoshi Akimasa (Meisho), Secretary and son of calligrapher Yamakoshi Hiromichi

Lecture 2

Vowels and consonants, space and time. Vowels map out space, while consonants map out time. All together they form the universe, uchuu, where u represents vowels and space, and chuu represents consonants and time.

Waka by Empress Shoken. Among the many waka written by Empress Shoken is this.

Shikishima no Yamato kotoba wo tatenukini

orushizu hata no oto no saya kesa

Shikishima is the name for Nihon in traditional waka poetry. Orushizu hata is doing the weaving with the hata-ori weaving machine, and oto no saya is the beautiful sound of weaving. The empress implies that time and space are being created in harmony, and the country is doing well.

One hundred sounds of kototama. There are one hundred sounds (syllables) when fifty sounds are reflected in the sacred mirror. There are various folktales about kototama. For example, the folk hero Momotaro has a name that refers to the one hundred (momo) sounds coming out. His grandparents are Isanagi and Isanami [says Yamakoshi]. In another tale, Urashimataro tells about the Chinese visitor who came seeking the elixir of immortality. When he opened the treasure box, only smoke appeared – because he did not understand kototama. [Doesn’t this imply that kototama is the secret of immortality?]

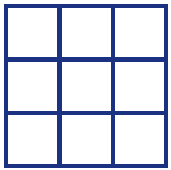

Yama symbol of eight spaces, kume symbol of nine squares. The yama symbol is the square containing four intersecting lines, one pair forming a ‘+’ and the other pair an ‘x’. These lines divide the square into eight parts, each an isosceles right triangle. The name ‘ya ma’ comes from the indigenous words ya meaning eight and ma meaning spaces. It is equivalent to kume: ku, nine; me, eyes; these ‘eyes’ are the points at the eight ends of line segments plus the point in the center. Yama can also be represented as a square divided into nine equal smaller squares.

[It is said that kume sennin immortals rode clouds around the universe. Sennin is written 仙人 and means immortal mountain wizard. The adjective kume may refer to wizards who understood kototama.]

The two lines that cross the yama square like a + is the symbol of the kami Kamimusubi. The other two lines that cross in an x form is the symbol of Takamimusubi. Both kami are needed to make sound and things.

The 9 father sounds (consonants) plus 5 mother sounds (vowels) together make 14 sounds, where 14 is toyo: to = 10 and yo = 4. [Toyo, as in Toyota, means excellent, bountiful. So the father and mother sounds together are excellent and denote prosperity.]

The joining of Kamimusubi and Takamimusubi is represented by the crossbeam as well as the the twisted rope shimenawa on a torii; it is a kuchinawa, a snake rope. These days it reminds us of the DNA helix.

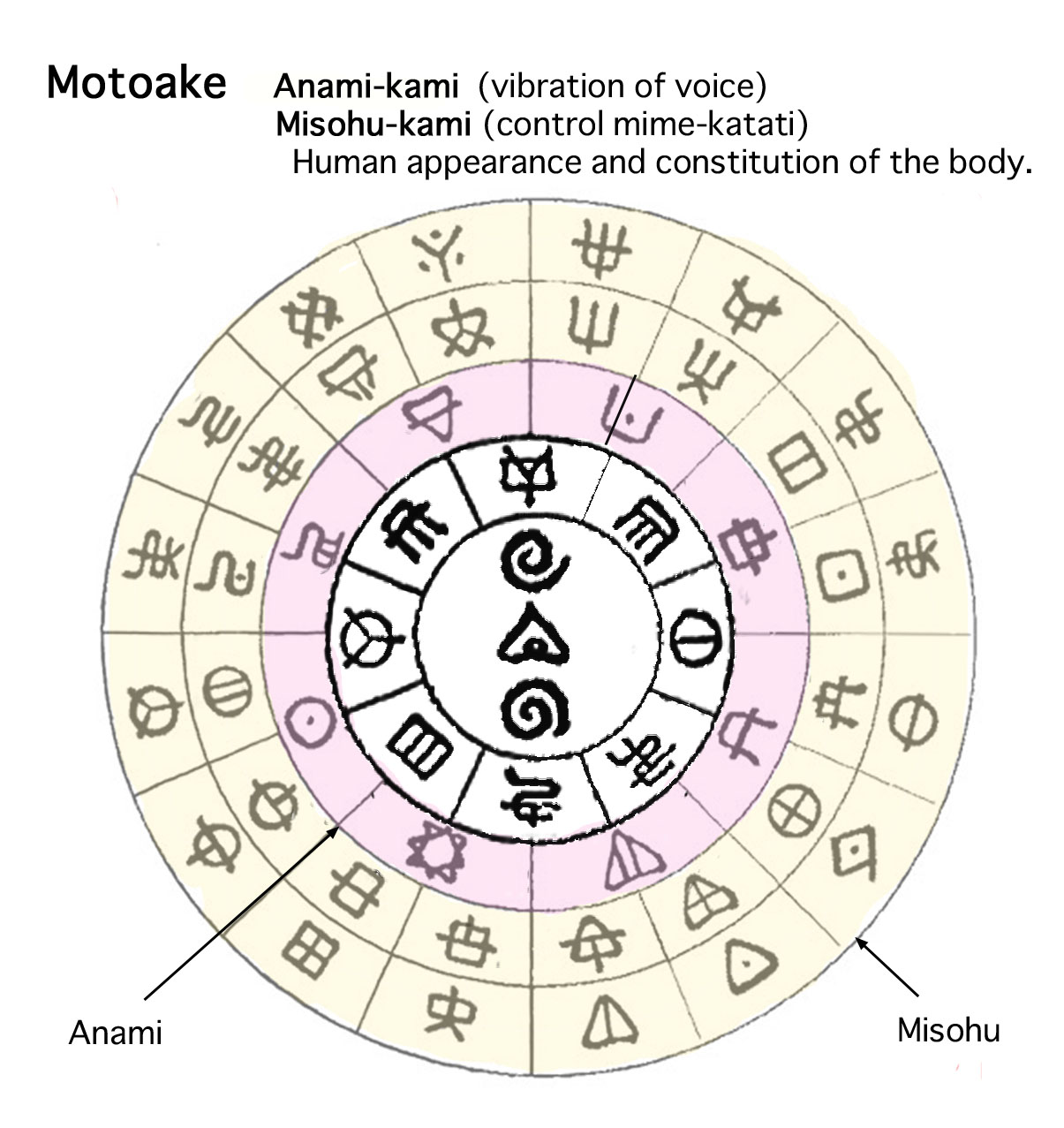

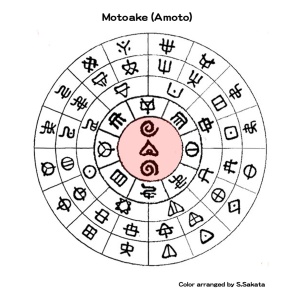

The Sound Chart: Amenominakanushi, Takamimusubi and Kamimusubi. The Amanoiwato [the sacred iwa rock-cave] is the human mind. To understand this, just listening won’t do. You must open your mind. The word iwa is i no ha (where ‘i’ means 5 or 50, and ‘ha’ means breath). The 50 sounds are fundamental (hado no moto). ‘Hado’ means vibration, and ‘moto’ means base. All vibrations from the universe enter the brain, and the hundred kami appear. A kami is power; for example the kami of water is the power of water. When we have musubi, the kami are connecting.

The sound U is the kami Amenominakanushi, which gives rise to the two kami Takamimusubi and Kamimusubi. Consider how U divides into A and WA. A is akarui, light, Takamimusubi. WA is shadow, Kamimusubi. A is clear like fire, and positive; WA is hidden like water, and negative. So the single sound of U separates into WA-A, mizu-ho, water-fire. [Mizuho is also the name of a large financial corporation in Japan.]

Takamimusubi makes things come out – recall that the T sound is a coming out sound. Kamimusubi makes things by connecting. Both kami are needed! They are dual (opposite) energies of U. When U divides into WA and A, the properties of WA and A are as follows.

WA – A

Kamimusubi – Takamimusubi

water – fire

female – male

negative – positive

right – left

down – up

unseen – physical

black – white

heat – light

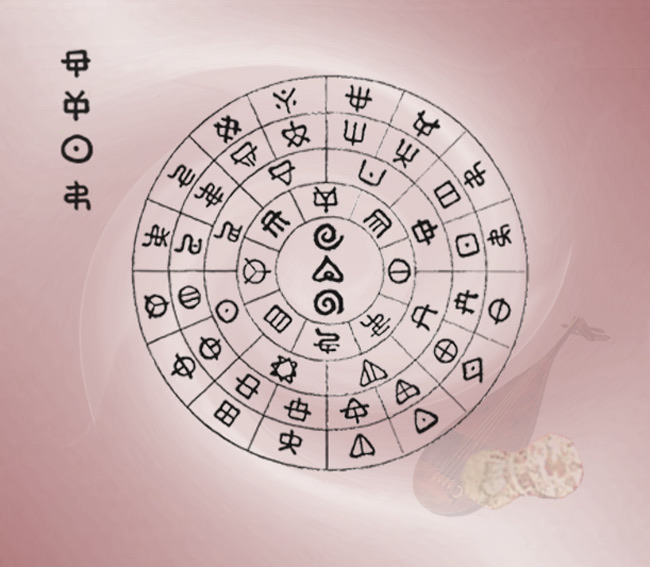

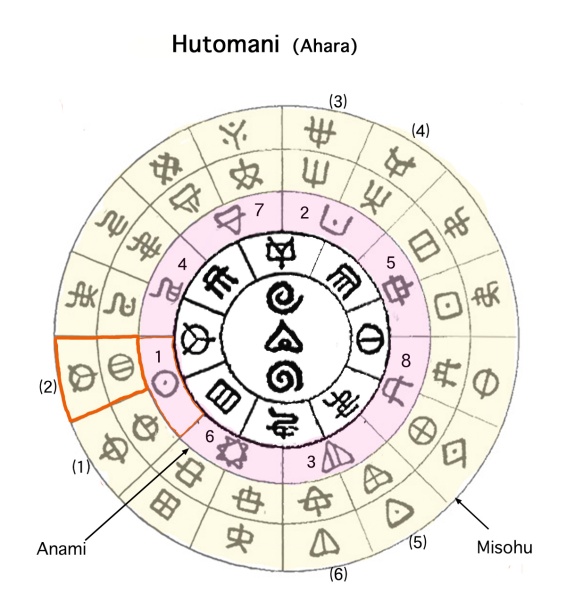

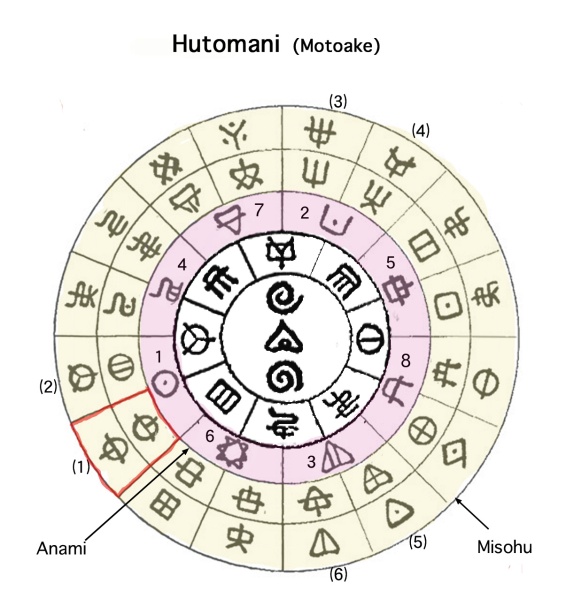

Futomani meaning. Let us now discuss what happens when we put our hands together when we pray or clap. A is the thumb of the left hand, WA is that of the right hand. The digits of the left hand represent the sounds A TA KA SA HA; the right hand represents WA YA MA RA NA. When we put our hands together we have the pairs A-WA, TA-YA, etc. One clap is ten sounds; two claps are twenty = futo, fu = two, to = ten, and represents the kototama of futomani, the twenty mana. Futomani is the joining of Takamimusubi and Kamimusubi.

Thus uchuurei the universal spirit enters the human head. Kami is the principle of movement of kototama.

Editor’s note: At the end of this lecture, Yamakoshi is describing the vibration of the universe as kototama. Vibration is movement, as in the above final statement. Or more precisely, the movement of kototama is the vibration of energy which we call by the name kami. Here, Yamakoshi is explaining his opening statements about Amanoiwato as the cave in the human brain, and opening the cave with kototama. He stated that kototama is the principle of every wisdom teaching. Do we see how he arrives at this conclusion?

We have learned the true meaning of Isuzu and now we know why it is as fine a name for a car as for a river. We learn here the greater meaning of Futomani. This basic meaning of futomani as the twenty energies is part of the kototama teaching. The use of futomani to mean divination is an application of kototama knowledge to analyzing a situation and determining an optimal outcome in harmony with the universe. Yamakoshi does not go into it here, but it is well known in kototama circles that the numerals hi, fu, mi, yo, i,… (one, two, three, four, five,…) are themselves powerful kototama syllables.

***

In the previous post on the Ahara waka, we connected the terms: ahara,

In the previous post on the Ahara waka, we connected the terms: ahara,

The Hutomani was compiled by Amateru Amakami. In order to have the best document for use by the leaders of society, Amateru compiled 128 waka verses. He was in his last years of life. The Kagami-tomi Amano-koyane assisted.

The Hutomani was compiled by Amateru Amakami. In order to have the best document for use by the leaders of society, Amateru compiled 128 waka verses. He was in his last years of life. The Kagami-tomi Amano-koyane assisted.