Editors Note: This article is about the book, Annotated Mikasahumi and Hutomani, by Yoshinosuke Matsumoto, editorial supervisor, and Mitsuru Ikeda, editor; published 1999 by Tenbosha (Tenbou Company); in Japanese:ミカサフミ・フトマニ Mikasahumi – Hutomani , 松本 善之助 (監修), 池田 満 , Matsumoto Yoshinosuke (author), Ikeda Mitsuru (series editor), 1999. We have translated the first ten pages into English.

*****

Preface

Mikasahumi and Hutomani were edited long before kanji was introduced to Japan. Both books are very precious because they explain basic ideas of how the country of Japan was established.

It is unfortunate that not all volumes of Mikasahumi were found. Seven more chapters existed around the middle of the Edo era. However, time just flew while trying to find them. Of course, the books we have already found give us great value without doubt. This is why it took twenty-seven years before publishing these two books. This time we are publishing not only the remaining volumes of Mikasahumi, but also selected quotations from them. We wished to find all volumes of Mikasahumi, but we could publish only those quotations from what we had.

I would like to thank Mr. Naohiro Nonomura who loaned us the precious original copies of Mikasahumi and Hutomani. I also wish to thank Daigu Library of Ryukoku University who repaired the books and conducted difficult searches. I also send heartfelt gratitude to Mr. Akiyoshi Karasawa of Tenbosha who agreed to publish these books which are probably difficult to sell although very precious.

September 1, Heisei 11 (1999) by Matsumoto Yoshinosuke

These three books: Hotuma Tutaye, Mikasahumi, and Hutomani comprise the extant documents written in ancient Japanese Wosite.

EXPOSITION

1. Synopsis of Mikasahumi

In ancient times, the eighth Amakami Amateru said,

ware mukashi amenomichi yeru kagunohumi

“I learned Amenomichi by Kagunohumi long ago.” However, the Kagunohumi document has regretfully not been found. Therefore, it is difficult for us to understand the journey of Amateru’s mind. So, this introduction of Mikasahumi is important. People who want to understand its value need to know its contents.

The most important matter for the existence of a clan was to establish Ooyake [a principle of public administration]. This principle has lasted from the time when Amanokoyane also known as Kagaminotomi [Advisor of the Mirror] and his descendants served as priests of Ise Jingu or as Fujiwara ministers. We understand that Ooyake, which an ordinary person has difficulty in understanding, is the real purpose of existence for the Kagaminotomi. That is, Ooyake is the principle for which Kagaminotomi held responsibility. The eighth Amakami Amateru realized the depth of Amenomichi in Ooyake.

Mikasahumi, which Amanokoyane made sincere efforts to compose, fully explains the concept of Ooyake. It is the reason for the existence of Kagaminotomi. Therefore, we can trace the movement of Amateru’s mind through Mikasahumi.

Unfortunately, not all the volumes of Mikasahumi were found. Yoshinosuke Matsumoto Sensei and we students looked for them all over, but we had to publish this book based on what we found. It is still important to keep searching for the remaining chapters.

We confirm that Hotuma Tutaye and Mikasahumi were published at the same time and have the same world view becuase they have some of the same sentences. We left-lined the columns of the same sentences of Hotuma Tutaye and we also inserted annotations.

2. Synopsis of Hutomani

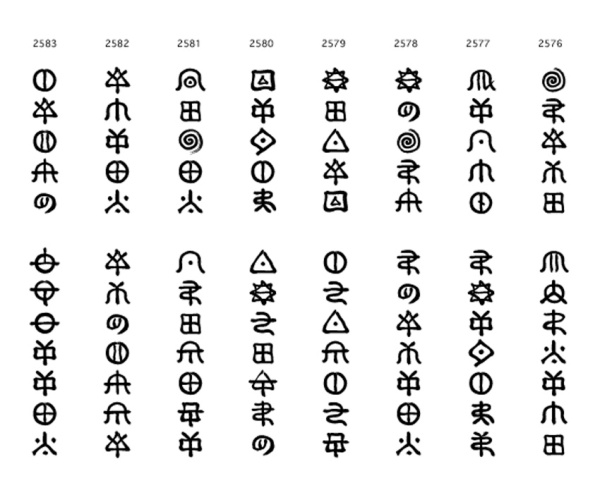

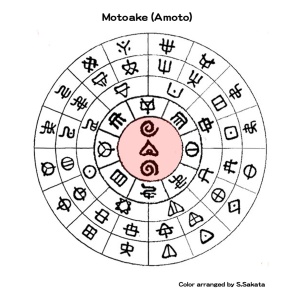

Hutomani is a book of poems used for decision-making. Its basic structure is Motoake, represented by a diagram of how the universe was created. Motoake represents the essence of the universe and it symbolizes every phenomenon in the world. Each poem in Hutomani is attached to one of 128 symbols of Motoake. Since all 128 poems in Hutomani currently exist, we can see how they understood the world. Words cannot express the value of the Hutomani we inherited.

Hutomani was compiled by the eighth Amakami, Amateru, when he retired and was in the last years of his life. This is the Hutomani which currently exists. However, in Hotuma Tutaye, only two of four examples of symbols (shichiri, akini, akoke, shihara) match the contents of poems in Hutomani. That is, akini (20-23) and akoke (20-52) have similar contents of poems seen in Hutomani. Interpretation of ancient times for shichiri (10-1) is seen in Hotuma Tutaye. A different interpretation of shihara (27-45) of Hutomani is written in Hotuma Tutaye.

After considering these things, we understand that the basic theory of Hutomani is based on the Motoake diagram, and the interpretation for each symbol changes depending on situations and times. Therefore, the method of Hutomani comes from the symbols in Motoake, namely Amenokokoro, and represent phenomena of the universe. The poems in Hutomani help us to interpret them.

3. Transmission [of Documents]

a. Nonomura Family [Mikasahumi, Hotuma Tutaye]

Eight chapters of Mikasahumi and Nonomura Ryuzo’s Hutomani were kept in the mud-walled storehouse of an old family of beautiful Takashima town on the north-west coast of Biwa Lake. Three volumes consist of seven chapters entitled Shinsaizanshoki in kanji, owned by Mr. Nonomura Tadahiro. The latter is a descendant of Nonomura Ryuzo who lives in Takashima-cho, Takashima-gun, Shiga-ken. These were the most important copies of the first seven chapters of Mikasahumi. The seventh chapter had the keys to the basic theory of Ooyake.

Waniko Yasutoshi who copied these volumes lived around the middle of the Edo period. He copied Hotuma Tutaye and attached a kanji translation. He also copied Mikasahumi and added a kanji translation. We should not forget that we can read the first seven chapters of Mikasahumi and Hanimatsuri no Aya because of his accomplishment.

In Syuusinseidenki Denrai Yuishogaki, Waniko Yasutoshi was said to have used a common name, Ibo Yunoshin. It must have been some kind of fate that the late Ibo Kichibei and Ibo Takao (who lives at Nishimanngi, Azumigawa-machi, Takashima-gun, Shiga-ken) found all volumes of Hotuma Tutaye by Waniko in Heisei 4 (1992). We refer for details to the Hotuma Tutaye by Waniko (published by Shin-Jinbutsu Ourai Sha in Hesei 5).

Mr. Nonomura Tadahiro who owns the Mikasahumi by Waniko is a great-grand son of Nonomura Ryuzo who was a samurai retainer of Oomizo Han during the last period of the Edo era. The castle of Oomizo Han of Wakebe Clan of Nimangoku was a center of culture situated at the south end of the large Azumigawa Plain during the Edo era.

During the last period of the Edo era, the Keio period, all volumes of Hotuma Tutaye and the remaining volumes of Mikasahumi were found in Nishiyurugi-mura and turned in to the Oomizo Han, and were put in the charge of a temple-shrine. After the turbulent end of the Edo era and Meiji Ishin and the abolishment of the Oomizo Han, Nonomura Ryuzo became chief priest of Mio shrine. He is described as a healthy eighty-five year old man in Kondo Seisai Zenshu (Kokusho Kankokai, Meiji 38). All documents that belonged to Oomizo Han were transferred to Shiga-ken, but regarding the Wosite documents, Nonomura Ryuzo made copies, and the Hotuma Tutaye was given to the Hiyoshi Shrine of Nishimagi as an offering in Meiji 22. Of the remaining Wosite documents, a copy of Hutomani was handed down to Oomizo Naohiro, the current head of the Nonomura family. This copy of Hutomani is the oldest complete copy that we now have. Nonomura Ryuzo passed away before he could make a copy of Mikasahumi which was handed down to his descendants.

b. Ogasawara Family [Hutomani, Hotuma Tutaye]

The Ogasawara family in Uwajima, Shikoku, are well known to have kept the Hotuma Tutaye. They also had Hutomani handed down from their ancestor.

Ogasawara Michimasa encountered Hotuma Tutaye when he visited the west of the lake area during Bunka or Bunsei period of Edo era. He realized the importance of this document. He wanted to let the world know that it would supplement the Nihon Shoki by publishing Kamiyokan Shuushin Seiden (kept at the Kokuritsu Koubunshokan National Archive).

Ogasawara Nagahiro, a descendant of Michimasa, earnestly studied the Wosite documents. Nagahiro was assigned to be a priest at Akama shrine located at the Kanmon channel, and he copied all volumes of Hotuma Tutaye; he returned the old version of Hotuma Tutaye without translation in kanji to Takashima-gun. (They were damaged by mice and lost around Showa 10.) Nagahiro visited Takashima-gun with his strong passion and will, and he saw them when he was 74 years old. He knew that Wosite documents were true writings.

Ogasawara Nagatake was a nephew of Ogasawara Nagahiro. He is the one who really began a modern era search. He copied all volumes of Hotuma Tutaye, and he created a method of comparing these books. He also tried to ask Sasaki Nobutsuna to acknowledge Wosite documents. It is to his credit that Hotuma Tutaye is kept in the National Archives. He also left us a precious copy of Hutomani.

c. Fusen [Kasugayamaki, Mikasahumi, Hotuma Tutaye]

Fusen, a priest in Nara, left us the oldest Wosite documents which have been found so far. Considering that he was already quite elderly when he published Kasugayamaki in Anei 8 (1779), he was one of the earliest scholars who studied Wosite documents in our times, as far as we know. We are strongly interested in the sentences quoted from Wosite documents in his books, Kasugayamaki and Asahishinki. We really hope that the original Hotuma Tutaye and Mikasahumi which Fusen used will actually be found. Only Toshiuchi ni nasukoto no Aya was found, and we were able to publish the contents of this oldest Wosite document with the permission of Ryukoku University.

[End of p10]

*****

***

Wosite Literature

Wosite Literature A Utuho “space” Originating energy/process

A Utuho “space” Originating energy/process U Ho “fire” Burning energy/process

U Ho “fire” Burning energy/process E Mitu “water” Flowing energy/process

E Mitu “water” Flowing energy/process

The Hutomani was compiled by Amateru Amakami. In order to have the best document for use by the leaders of society, Amateru compiled 128 waka verses. He was in his last years of life. The Kagami-tomi Amano-koyane assisted.

The Hutomani was compiled by Amateru Amakami. In order to have the best document for use by the leaders of society, Amateru compiled 128 waka verses. He was in his last years of life. The Kagami-tomi Amano-koyane assisted.